Start Small and Keep it Simple: Overview

Keep it simple stupid KISS in software development isn’t always easy. After 10 years of maintaining and evolving a little search engine, it’s time for a review.

Overview #

The project started with a question from a former colleague whether we could build a search engine about planned topics in journals, magazines, and newspapers. Me as a developer has a an instant desire to answer such a question with a clear Yes: greenfield projects are great playgrounds, places to learn and hone one’s skills.

The tech stack started with a proof of concept using CouchDB, Elasticsearch, Spring Framework and Wicket. Wicket had been replaced by an Angular frontend after a while, plain Spring became Spring Boot, but the rest stayed the same until today.

We’re currently running the services on DigitalOcean, with the provisioning and deployment being modeled in Ansible. Docker replaced Debian/Ubuntu packages some years ago, and Terraform has been added to the mix since 2022.

Simplicity Works #

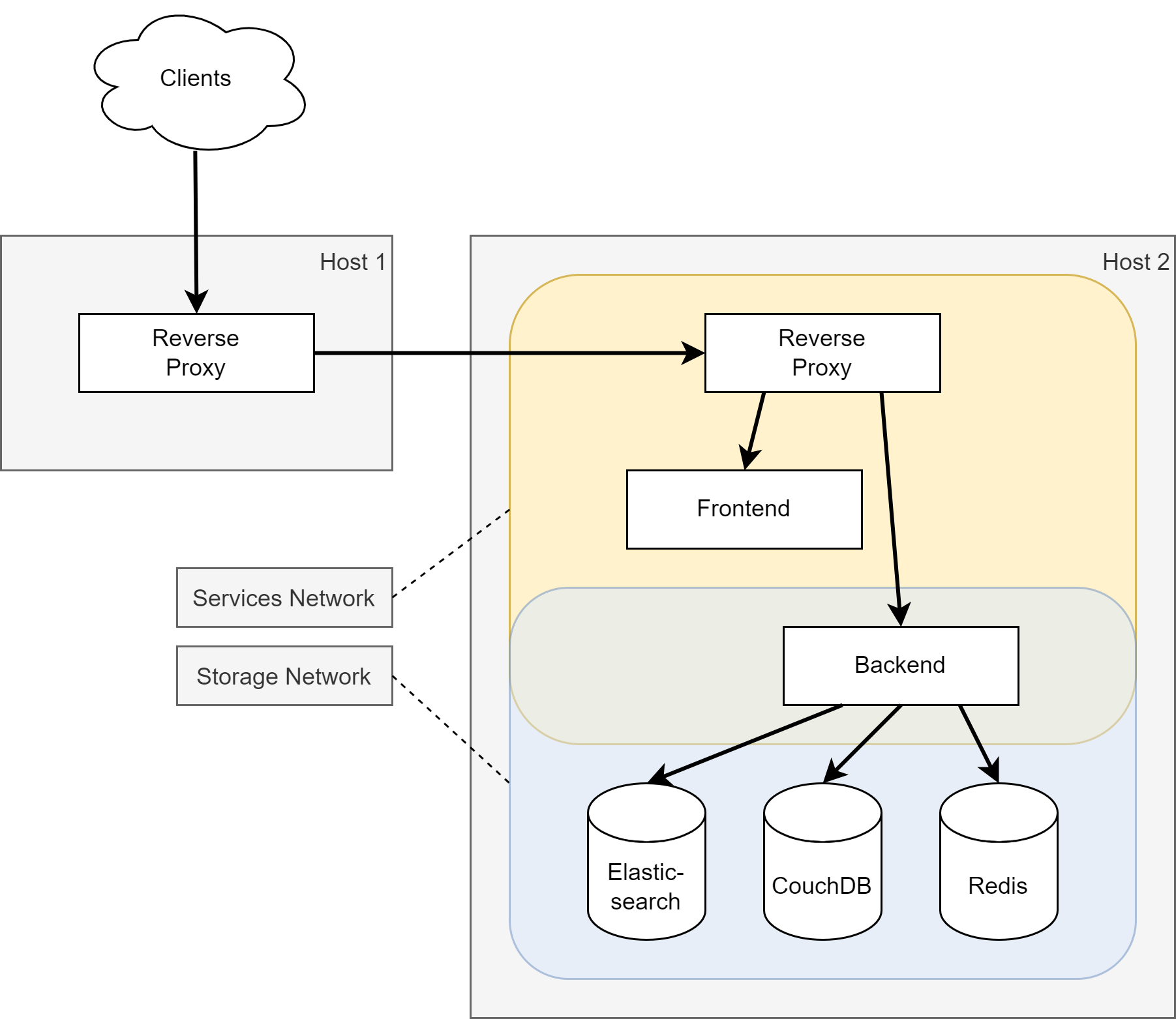

Pictures tell more than words, so here is an architectural overview of the whole setup:

Yes: you’ll notice many best practices missing. That’s partially for simplicity of the diagram, but mainly due to the simplicity of the actual architecture. We usually deploy services like Elasticsearch and CouchDB in a cluster, but in this case it’s really just as simple as on a local developer machine. The Frontend, Backend, and the reverse proxies should also be deployed as replicated instances for better scale and elasticity - but they’re not.

We certainly won’t stand against a DoS attack, but the application just works for the registered customers with a complete feature set, and anonymous users with their restricted feature set. A whitelabelled variant is included in a partner’s product, so there are additional users not directly subscribed to our appliation putting some more load on our application.

In fact, this is not about the technology being simple. It’s about a clear product with simple, yet effective features: similar to the input field on Google Search, a user only has to enter a query and optionally change some filter settings like date ranges or the kind of publication. Technology follows the product’s complexity - well, at least the developers or engineers shouldn’t artificially make the stack more complex than necessary.

In this case, focused on the user’s needs, all we need is a simple query, some pagination, maybe an export feature, and the option so save the query parameters for easy re-use. From the administrator’s point of view there’s an import feature to keep the data up-to-date, and a user management to maintain subscriptions. The developer, yours truly, is interested in short development cycles and the chance to understand the codebase even after some weeks of inactivity. With patterns like Infrastructure as Code (IaC) a developer can focus on the exciting parts and leave the boring processes to automation.

The fun part: along the years, several other tools grew due to individual requirements, and if you already followed my activities at github.com/gesellix, you won’t be surprised that those add-on projects are available as open source. As an example: we started with Debian packages to distribute the application artifacts, but migrated to Docker containers quite quickly. You can recognize that shift in the contributions to the Gradle Debian plugin compared to the development of the Gradle Docker plugin. I won’t go into the details about the older tools, which I might not even use myself anymore, but I still try to keep them up-to-date and usable for other people.

What’s under the hood? #

Back to the search engine. This year, we took a fresh start for the whole provisioning layer: due to some hosts being old enough for retirement and a major Elasticsearch upgrade in our backlog, we opted for true IaC by introducing Terraform and its DigitalOcean provider. A more spontaneous upgrade happened to the CouchDB from 1.6 to 3.2, which was a simple task given the straight forward CouchDB concepts… did I mention that I love CouchDB?

So, we’re going to describe a fully working setup (from scratch!) with the only requirement of a database backup being imported to the fresh installation and the search index to be created from that fresh database.

I’ll provide some code down below and if you’re going to try the setup for your own projects, than you can use DigitalOcean’s referral program. Simply follow this referral link to sign up, which helps yourself starting with a $100 credit, and myself earning a bit of money as well. Thanks!

With Terraform performing the initial deployment of hosts, domains, low-level stuff, and some basic cloud-init based configuration of the operating system, we need another step of configuring the operating system and adding required software packages. Ansible has served us well for the past years, so we still use it for provisioning and some deployment tasks. Provisioning is very simple, because we only need to install the Docker packages on top of some core packages. Everything else runs as a Docker container, being configured and run through Ansible modules.

Docker allows us to choose between manually maintaining containers (docker run)

and orchestrating tasks (docker service create) via Docker Swarm.

Well, we don’t actually choose one of those modes, but use both:

for our long-running processes like the storage layer, we use standard containers.

Updating those instances usually requires downtime - and that’s fine for us, because we don’t

update or re-deploy the databases very often.

Things look different for the Frontend and Backend services: this is where features or

bug fixes are added regularly, so we need a more convenient way of updating those services.

We want it to happen in an automated fashion.

Docker Swarm mode helps a lot and allows a zero-downtime deployment via declarative configuration.

This is similar to Kubernetes - only less complex, with smaller resource requirements,

and matching our needs.

The Frontend and Backend services are initially deployed via Ansible, but we don’t perform service

updates that way: as long as we only want to update the parent image, we can use Docker’s

service update api. The Docker api shouldn’t be exposed to the internet, so we added a

tiny webhook service with access to the Docker engine. That webhook service accepts

authenticated requests from a GitHub workflow. The GitHub workflow can be triggered on

pull-request merge or even from a feature branch to trigger a preview deployment in

a non-production environment.

Everything we mentioned above isn’t exposed to the internet. To make the application usable for customers we added Traefik as reverse proxy. Traefik works great together with Docker (and Docker Swarm) and helps with the boring stuff like certificate management via Let’s Encrypt.

If you look close enough, you’ll notice two colored boxes in the picture above: we added two Docker networks to segregate the storage and the application layer, so we can reason about smaller parts of the whole stack and reduce the risk of failure in case of security issues or human error. The storage layer won’t ever be accessible from the internet or even the publicly available reverse proxy. The backend is the only service running in both networks.

Before we go into details about each part of the stack, let’s explain the use case for each storage service: the CouchDB is our primary database with the actual data being queried by the customers and also containing the user and configuration databases. We don’t use the CouchDB for the full-text queries, though: this is where Elasticsearch shines. During the import of updated data, we write everything into the CouchDB database and Elasticsearch. This is convenient in case of data loss in Elasticsearch, because everything is available as JSON in CouchDB, easily and fast to be synched. CouchDB is very easy operate (ok, it became a bit advanced since version 2 with its clustered setup, which is still configured as a single master node in our case) and can be backupped by copying the data volume. Replication to another instance works very well, too! The Redis database is for ephemeral user session metadata. Nothing exciting on that part.

Show me the code! #

After that overview about each part of the stack, we’re going to peek into the actual code. We’re going to describe the details in upcoming articles, along with actual code for you to play with or start your own projects.

The next article will cover Terraform and parts of the initial provisioning. So, stay tuned and in case you already have some questions, just get in contact via twitter.com/gesellix!